Looking at the Bigger Picture

We deal with common assaults frequently. Often a client will come to us with instructions right off the bat to enter a guilty plea and prepare submissions in mitigation of their sentence; without even having heard our advice or having us review the brief of evidence. Most of the time, it’s because there has been some form of physical contact between them and the complainant, and they think that’s all it takes.

They think they’ll save money, time and stress by pleading guilty and being done with it quickly; and want to avoid what they think will be a hopeless defence at all costs. In some cases, we can’t manage to convince them otherwise; the failure to defend or the guilty plea can lead to further complications, such as the commencement of civil proceedings by the complainant seeking compensation; or an apprehended personal or domestic violence order application, plus the financial and legal implications that follow. We thought we’d dispel some myths to put a stop to this…

Please note that here, we are talking only about common assault, i.e. a basic assault charge without any additional element, such as aggravation or the infliction of actual bodily harm. Those are different charges for a different blog post.

With common assault, the following four fundamental elements make up the charge; and all of them must be proven by the prosecution beyond reasonable doubt in order for the charge to stick:

1. A striking, touching, or application of force by the accused to another person;

2. A lack of consent to that action on the part of the other person;

3. Intent or recklessness on the part of the accused, in the sense that the accused realised that the complainant might be subject to immediate and unlawful violence; yet took the risk that that might happen and proceeded anyway; and

4. That the accused had no lawful excuse for their actions.

The above example covers common assault involving actual battery only; as opposed to a situation where only the threat of battery is in issue. Where only a threat is concerned, the focus of the third element shifts to invoking an immediate fear of unlawful violence; which is another discussion altogether for another time.

The first element and what might be required to prove it is obvious.

However, the existence of the other three necessary elements automatically dispels the myth that physical contact is all it takes – there are still grounds to defend common assault, even if the accused has actually hit the complainant. The first element is also obvious, whereas the other three, although appearing obvious, are slightly greyer areas…

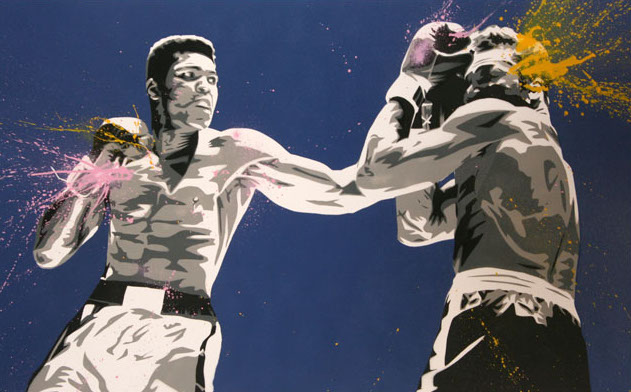

In some circumstances, consent might not be relevant, or may be impossible for the accused to rely on. For example, where people enter into a consensual fight with the intention to inflict actual bodily harm, they will automatically be guilty of an assault. However, where they do not intend to inflict actual bodily harm (another legal term open to interpretation); the conduct of the parties might imply that consent was present. Such conduct includes, for example, sparring, boxing, contact sports and general “bravado”.

Next to consider is intention or recklessness.

Note that the test here is subjective, meaning the prosecution has to prove that the accused actually was acting intentionally or recklessly; as opposed to proving that the hypothetical reasonable person would have been in those circumstances. This requires, firstly, proof that immediate and unlawful violence crossed the accused’s mind at all. If the incident took place too quickly, or was a knee-jerk reaction to striking by someone else, then that will be difficult to prove.

Finally, there are lawful excuses.

Self-defence is the most obvious example – the notion that one had to act in the way they did in order to defend themselves or others. Interestingly, if self-defence is raised by a defendant on the basis of evidence already in the prosecution case; the burden of proof switches back onto the prosecution to prove that the defendant wasn’t acting in self-defence. If self-defence is made out, it will provide a complete defence to the charge. There are additional lawful excuses too, such as an amount of reasonable force required to push through a crowd, and so on.

So, common assault is not as simple or hopeless as it may seem. If you feel that one of those four elements above isn’t made out; the chances are it may be worth defending.

At Green & Associates, we are experts in applying for no convictions; and have an excellent success rate in achieving this for our clients. Regardless of the charge, we are ready to be in your corner and assist you during this uncertain time. If you or someone you know needs assistance with a similar case, contact our office today.